The best of Engadget's Big Picture in 2019

I love doing The Big Picture series for Engadget, even though it can take a lot of hunting to find a striking photo with a tech angle. I believe in the idea that, by creating some emotion, dramatic images help us grasp heavy concepts in a way that words alone can't.

Another is that I learn a lot of interesting stuff while researching them. That includes things about art, astronomy, science and even weaving. That information seems to stick in my head as it's indelibly associated with a powerful image.

Many of this year's Big Picture images make interesting statements about the impact of technology on humanity. And although some of the images were created by accident or without artistic intention, they're often full of symbolism and irony like any other works of art. I think a great example of that is the first item on my list.

Why Garfield phones have littered French beaches for 35 years

Can any image convey the folly of rampant consumerism more perfectly than this? The character itself was "a conscious effort to come up with a marketable character," according to its creator. It worked, and the phone was just one of many terrible Garfield products dumped on the public in the '80s. In 1983, a container full of the gaudy phones fell off a ship near Brittany, France and has been disgorging them into the ocean ever since.

A volunteer group finally found the source in a cave near a town called Plouarzel, but the tide makes it impossible to remove them. Just one glance at this juxtaposition of nature and trash tells us everything we need to know about human stupidity (and the '80s).

EV batteries are born in Chilean evaporation ponds

Here's what a good image can do: almost every time I think about lithium-ion EV batteries nowadays, this NASA/Landsat/Geological Survey satellite image pops into my head. Before I did the article, I had no idea how lithium was produced. Now I understand that much of it comes from lithium brine in salt flats around the Andes mountains in Chile and neighboring countries.

Since it's taken from the surface (and not underground mines) like fleur de sel , you can clearly see the scale of the operation. It consumes a lot of water, creating conflicts with indigenous people of the region. What's worse, scientists don't know the future impact of such operations. "When people ask me, 'Is the water going to run out?' I tell them, 'The truth is, we don't know," said hydro-geologist Mariana Cervetto.

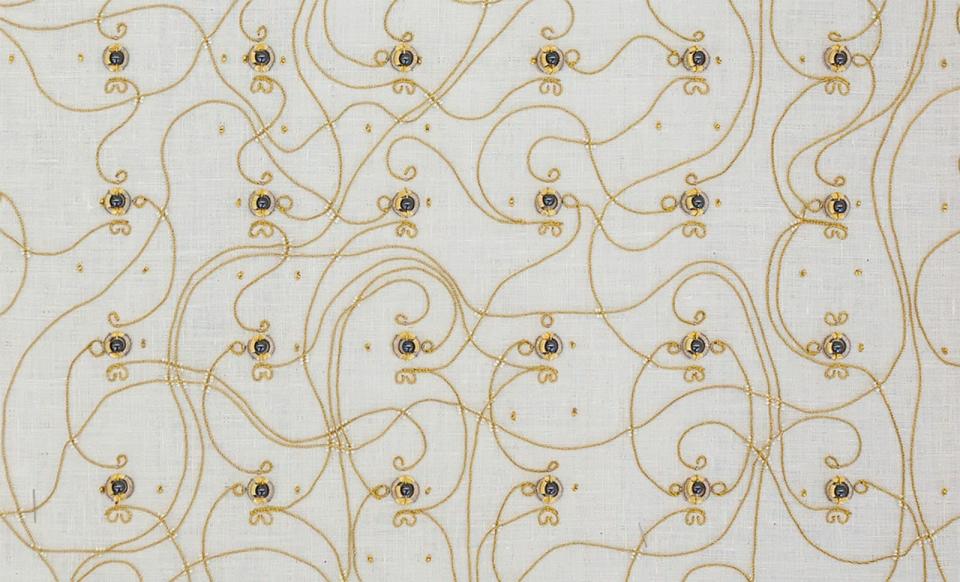

Textiles become circuits in 'The Embroidered Computer'

The Embroidered Computer is a working, 8-bit electromechanical computer made from gold, linen, hematite, wood, silver and copper. It has flippable relays much like the ones used in mainframes before semiconductors came along. It's one of the most striking examples I've seen of bringing form to function and vice-versa.

"Through its mere existence, it evokes one of the many imaginable alternative histories of computing technology," artists Irene Posch and Ebru Kurbak wrote. "Traditionally purely decorative, their pattern here defines the function. They lay bare core digital routines usually hidden in black boxes. Users are invited to interact with the piece in programming the textile to compute for them."

Facing your AI self at the 'Neural Mirror' art installation

Corporations don't see you as a person with a desires, needs and a rich inner life. They simply see you as a collection of data that helps them sell products. An Italian design studio has created a mirror that lets you see yourself the way they do, so perhaps we can better understand how we're being manipulated.

The "mirror" is actually an OLED panel with a reflective coating and depth-sensor camera that can act as both a mirror and display. It generates a Matrix-like doppelganger of the visitor, while showing creepy data about their ethnicity, facial geometry, facial expressions and more. "Artificial intelligence extracts all of our behaviors in a shady way then transforms them into a form of wealth for corporations," Ultravioletto's Bruno Capelzzuoili told Dezeen. "Here this process is well declared and explained to the user. They can see in real time what kind of data we are capturing."

One of these models doesn't exist

We're sold beauty products based on a connection with human models, but those days could be numbered. Earlier this year, a virtual model and Instagram "star" named Imma (center) appeared in a makeup spread for Kate cosmetics with two human models.

While you might quibble over her realism, there's no denying that Imma is at least on her way out of the uncanny valley. The implications aren't great for folks who work in this industry. Brands are starting to rent out virtual models like Imma and another called Miquela, depriving real models of paid gigs. Worse, as Facebook just found out in a recent disinformation campaign, fake people could be used to manipulate users without leaving any kind of human paper trail. "Did you hear it with your own ears? Did you see it with your own eyes?'" said actress Heidi Johanningmeier. "We'll never be able to trust that again."

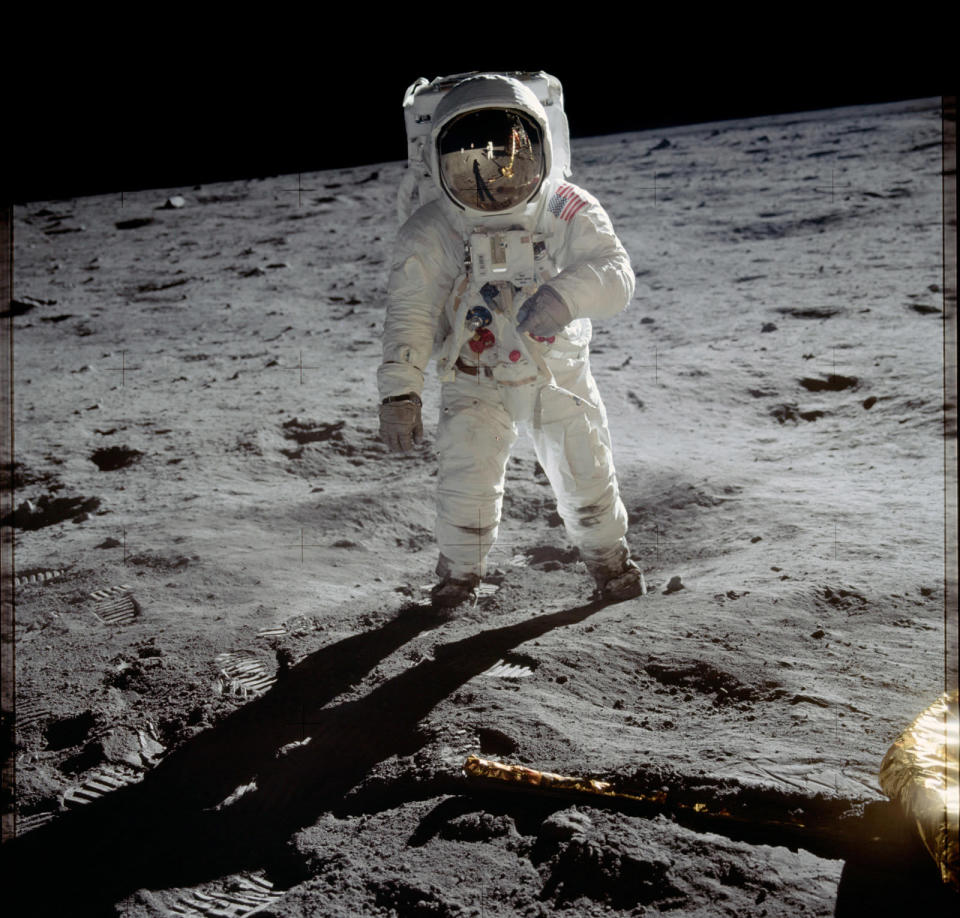

Neil Armstrong's Buzz Aldrin photo is unparalleled in art

Sometimes you don't need to be an artistic genius to take a great photo, you just need access to the subject. After white-knuckling the "Eagle" lunar lander to the Sea of Tranquility, Neil Armstrong was somewhere no other photographer had been: the Moon. He also had a perfect subject, fellow Astronaut Buzz Aldrin, sporting a photogenic outfit that was the most technically advanced ever created.

Armstrong wasn't just a tourist with a Kodak instamatic, though. He had an advanced Hasselblad 500 EL camera and extensive training on how to use it. He learned well: the photo captures the moon's vast desolation while also conveying the wonder of the occasion. It paints the astronaut as an anonymous explorer, coming in peace to an unconquerable black and white world.

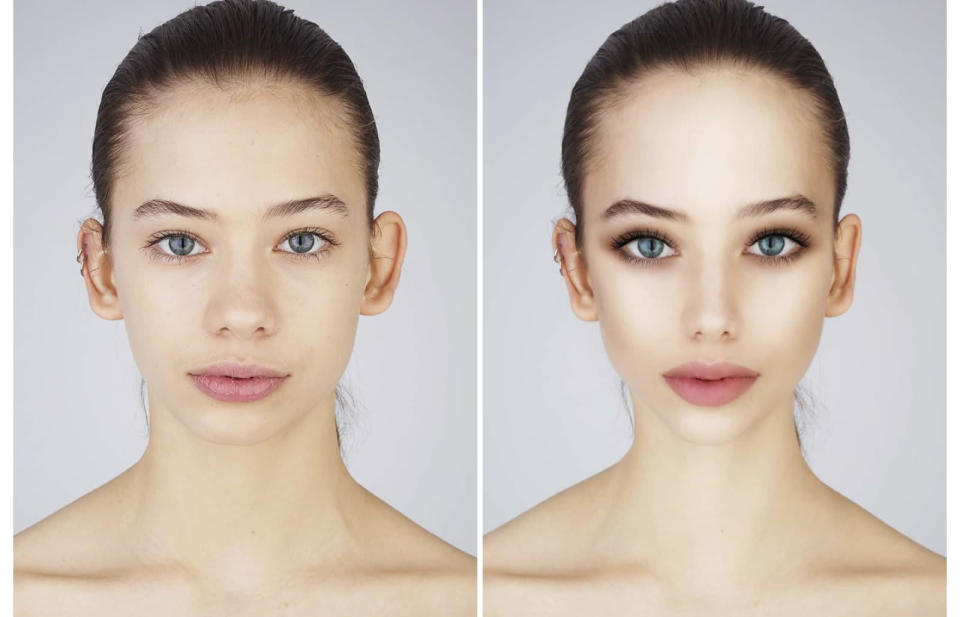

Selfie harm and the damage done

The Snapchat and Instagram generation might have more body dysmorphia than ever, and a photographer known as Rankin wanted to explore that. He took photos of teens aged 13 to 19, then asked them to spend a few minutes editing the shots. So what happened? "People are mimicking their idols, making their eyes bigger, their nose smaller and their skin brighter, and all for social media likes," he said on Instagram.

All of this is facilitated by apps like Facetune, SelfieCity, Retouch me and others. "What you can do on these apps is way beyond what even a great photoshop operator can do," he told Bored Panda. "They're addictive [and] very impressive." No doubt, this kind of stuff can be fun if you're just messing around, but it can also become very dangerous. "It's when people are making an alternative or 'better' social media identity that this becomes a mental health problem," said Rankin.

ENGADGET'S YEAR IN REVIEW 2019